Drieu in Argentina: Borges, Love, Fascism

some bits from Pierre Drieu La Rochelle about his 1932 trip to Argentina.

Borges is worth the journey

Borges this, Borges that. I was told so many things about him in Buenos Aires! Some people confided to me that he was an intellectual. But they are all wrong, because what they mean is that he is intelligent; very intelligent.

Those who do not like intelligence often use the word “intellectual”. But we will not listen to them and we will continue to love intelligent people - for their rarity, for their vitality and for their versatility.

After all, to be intelligent means to be alive. You cannot be intelligent without being alive, and when someone is intelligent, he is first of all several other things. Have you ever seen a heartless intelligent man, an intelligent man with no sensitivity? If so, then he was not intelligent. Or maybe one believes that an intelligent man has no heart or sensitivity only because the manifestations of his heart and senses are so subtle they can go unnoticed.

Perhaps you are angry, my dear anti-intellectuals - because you have read Discusión1, but you have to read Borges' poems as well. So, how to get rid of it? Continuing to repeat: too intellectual?

Borges is endowed with an excellent nature. He is cheerful and sad, intelligent and sentimental, loving and deprived of everything. Nothing like a lecturer, but very learned, capable of analysis as well as lyricism. Why is that so? Maybe does this shock you?

Borges, who understands everything, has devastating passions. He is all passion because he is intelligent. An intelligent man does not fear his passions, and he serves them with a delicacy, a nobility in his choices that distinguish him from the fanatical idiot. Borges writes about the myth of Hell2 with an apparent insensitivity that can only offend fools. He knows very well that this dimension he denies has deep and real roots in the heart of man, and his own experience of Hell shines through, emerges from his vigorously incredulous lines.

A truly intelligent man - neither skeptical nor fanatical - with ideas, and behing these ideas a meditation that secretely nuances the most blunt expression.

It is reassuring to think that in every country there are some men with a well-made head. This rare world population alone justifies journeys.

And Borges is worth the journey.

Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, on the Atlantic, October 1, 1932.3

Addenda:

A letter to Victoria Ocampo from October 20, 1932

My article on Borges, for Megaphone, wasn't targeting you. I think you are, deep down, very rationalist and intellectual - in the good sense of the word -, that is to say not insensitive at all. His poetry proves that he is from this good species - a sensitive intelligence.

There is a lot of bruised passion in the first article of Discusión4.

A housebreaker's kiss

Drieu5

Between Winter and Spring6

I thought about becoming a communist. A strange kind of communism, to push towards decadence, towards the end of everything […]. And, all of a sudden, there was fascism. Everything became possible again, oh my heart. In 1932, I went to South America. […] When I came back, I was only interested in fascism, through reading, travelling, and conversation.

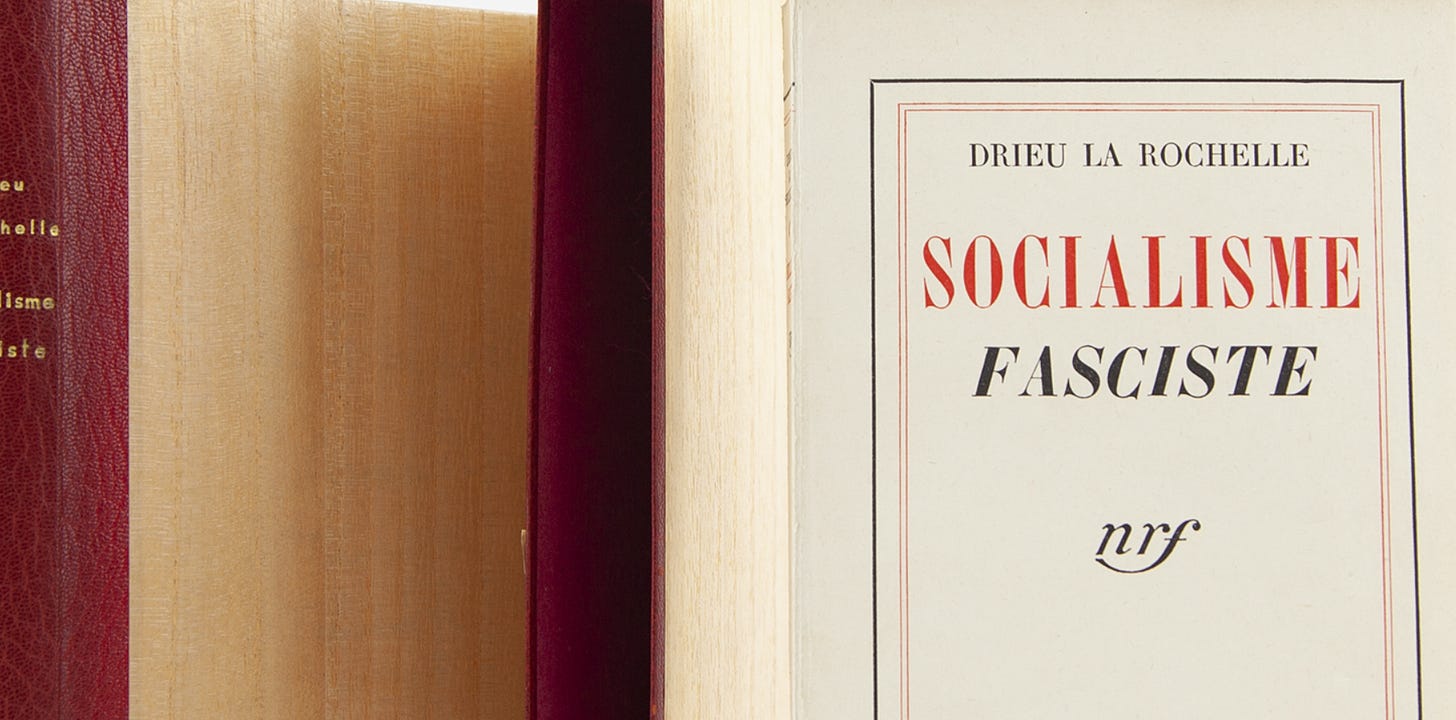

Socialisme Fasciste, 19347

In June 1932, I went to give lectures, to share my political musings in Buenos Aires. I took advantage of the opportunity, after the preface of Geneva or Moscow8, to renew my examination of conscience, by describing my whole journey so far.

In front of the young Argentinians who, like the young French, ordered me to be either a fascist or a communist, I first required a margin necessary for the intellectual to ensure his freedom of observation and his consideration of the wholes. From this convenient point of view, I analyzed the Italian and the Russian phenomenons with a vivid sympathy. Reviewing the whole history of the last fifteen years, the global importance of fascism appeared to me all the better. The Hitlerian movement, rumbling, was getting closer to the goal. I announced as certain the triumph of Hitlerism, if not of Hitler. I saw the inanity of the proletarian parties, an already old phenomenon in my eyes, that was being accentuated in a surprising way.

On the other hand, broadly speaking, I claimed to be a socialist. But in my own dialectical way, I defended socialism only by overcoming it; I always wished it were other than it was in the parties.

At that moment, my prescience was working hard, but was not able to free me entirely. I saw very well that socialism was growing through Hitlerism, and I was delighted because I now believed in the core of all socialist doctrine (apart from the proletarian Marxist one). But on the other hand, in the particular situation of France, I strove not to see further than the end of my nose, I believed that my socialism would force me to enter into the old hardened frameworks of the proletarian parties. From there came an apparent contradiction in my attitude: I analyzed with sympathy fascism and stalinism, and, moreover, I made a declaration of democratic socialism. It is that in truth I placed myself alternately at a worldwide and Franco-Argentine point of view.

In any case, in these lectures, I attached myself more than ever to a fundamental idea, which I have certainly helped to spread (alas! not quickly enough and not yet enough), which proves the homogeneity of my political thought and places me above the reproaches that can be made to me on the details of my quasi-immobile oscillation, and that is the parallel between Moscow, Rome and then Berlin, and now Washington - between stalinism and fascism. I profoundly believe that stalinism is a half-fascism and fascism a half-socialism. […]

But what I then thought for Europe, I was not yet capable of thinking it for France. Upon my return, I found myself more to the left. I was also drawn by my friendship for Bergery9, who seemed to me to bring into action the inclinations I had entertained by the fireside with intellectuals like Emmanuel Berl10, an old radical, and Jean Bernier11, a dissident communist. Moreover, by attaching myself to Bergery, I had the clearly stated intention of making him go as far outside himself as I had traveled outside myself. We were both groping for something that would free us and satisfy us. He dragged me, one evening, when I was lecturing myself to join the Socialist Party, to a meeting organized by the Amsterdam committee to protest against a shoot-out of proletarians in Geneva. I cannot say that I was at ease there. I feel as embarrassed in an exclusively proletarian meeting as in a millionaires' salon. I am frightened by all things entirely self-centered, which ferociously and lazily indulge in themselves. If I had spoken, despite the supleness of my manners, I would have made some noise.

There is the deep social passion, and the point of application on which a lack of personal experience or the immaturity of the political situation allows one to be mistaken.

Suddenly, thanks to the Hitlerian explosion, thanks to the corporate evolution in Italy, to the approaches of February 6 in France, I saw a side road for my socialism. And at the same time I found my spirit of 1920 that I had had to put in my pocket like so many French people for ten years. But I found it enriched forever by my European views, by my meditation on the dangers of war and economic division, and by my long-standing concern between rich and poor.

Published in 1932, untranslated in French before 1966. Its content (15 articles on literature and film) can be broadly found in the first 150 pages of the Penguin volume of Borges’ Selected Non-Fictions (ed. Weinberger), 1999.

The Duration of Hell, op. cit., p. 48 (p. 69 of the .pdf).

Published in French in the 11th issue of the Argentinean magazine Megáfono of August 1933. The text has been reissued in the Cahier de L’Herne : Borges, 1964, p. 105. The 1989 pocket reedition of this Cahier de L’Herne does not contain it, but the 1981 full-sized one does.

Probably La Poesía Gauchesca, not contained in the French version (a couple of essays focusing on Argentina having been replaced by essays on French literature).

in Victoria Ocampo and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, Lettres d'un amour défunt (1929-1944), 2020, p. 126. Drieu was invited in Argentina by his lover Victoria Ocampo, whom he met in Paris in 1929, to give lectures to Argentineans in 1932. He embarked in May 25 and stayed there until October. His lectures were about “The crisis of democracy in Europe” according to historian Guilhem Olivier (p. 48 of this article, notes 3 to 5; according to it [notes7 to 9], Borges’ anecdotes on a Bolivian 1860 dictator inspired the theme of Drieu’s 1943 novel L’Homme à cheval, but Victoria Ocampo says it was rather the ethnologist Alfred Métraux, with whom he went on a hike in Northern Argentina).

« Entre l’hiver et le printemps », NRF, April 1942, quoted in Sur les écrivains, 1964, and in an article about The theme of the Chief in Drieu.

Genève ou Moscou, 1928. Antelope Hill Publishing translated it.

Radical [in the French sense] socialist, close to the 1930s French movement of the Young Turks Jouvenel was a part of; he went on to be a collaborationist during World War 2. About these interesting fates, see Philippe Burrin’s La Dérive fasciste [“The fascist drift”]: Doriot, Déat, Bergery, 1986, and Simon Epstein’s Un paradoxe français : antiracistes dans la Collaboration, antisémites dans la Résistance [A French paradox: antiracist collaborationists, antisemites in the Resistance], 2008.

A French Israelite, friends with the surrealists, and of Jouvenel and Drieu, part of the late 1920s-early 30s French “fascist” milieux. He worked a bit for Pétain under the Occupation.

Close to the “critical” antistalinian and libertarian communists such as Boris Souvarine, he also worked with Georges Bataille in the 1930s.