Solitude of Buenos Aires

An article by Pierre Drieu La Rochelle in L'intransigeant, January 23, 1934.

I spent four months in this city of the end of the world and I have dreamed a lot. Where else can we better dream than to the end of the world?

This landscape of horizon truly is the end of the world. We wander around this city like a child, who would have fulfilled his absurd dream and, having really reached the horizon, would see up close around him this flat, long, bland thing, all elusive perspectives that the distance promised him.

Buenos-Ayres is flatness, but a staggering, grandiose flatness. A neverending flatness that starts again forever. In the periphery of this city - even more spread than London, with its two and a half million of inhabitants covering a bigger surface than the seven-million-large metropolis -, every other street is, one after the other, a new horizon. The ground is flat and on this flat ground, flat straight streets, drawn with chalk lines, bordered with flat, ground level houses.

It starts as soon as you arrive. You still think you're in the open sea and you're deep into an estuary that holds one hundred kilometers of width at Buenos-Ayres' level. And, if you don't see a thing, it is not only because the shores are far away; they’re also low.

But finally you get closer, and in the end the ground makes a layer over the sea. And by the way pride is there to anchor your eyes. Over this immense film of low houses, three or four rows of skyscrapers have been built - twelve-story, fifteen-story buildings: what's the difference. You keep your feeling of a mirage; you may think you see a city ruffling its feeble towers in the stretch of a puddle, just as at the desert. Because mirage doesn't betray the horizontality, and it does not promise mountains where there are none - desperatly none.

You disbark and, after kilometers of docks, you suddenly enter the heart of the city where your hotel is.

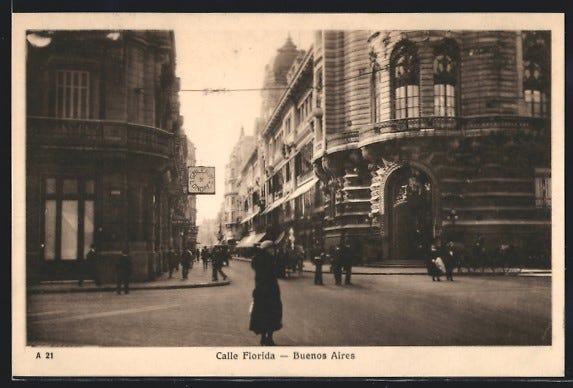

This center is also the old Buenos-Ayres. An Eighteenth-Century Buenos-Ayres, already drawn with chalk lines just as any other city of the two Americas; but a straight street recovers from narrowness what it has lost from straightness: intimity. The most lively street, the most busy, the most cherished by the Argentineans - Florida - is as large as Duphot street, or Daunou street.

So, if you were staying in the narrow and warm heart of the city, you could forget the first impression, dismiss the dizziness you beheld, forebode, and that awaits you. But if someday you go out in search of adventure, far away, then you will know what I want to say.

I am not exaggerating, Buenos-Ayres is exaggerating. This exaggeration is a passion, a madness, a vertigo.

Upon my arrival, I met an Argentinean poet who wanted to give me his city in all its excess, in all its grandeur and character at once. George-Louis Borgès made me take the subway. We headed outside at a random station, around midnight, and, under an enormous and diluted moon we started to wander in this immense straight-lined maze. We were walking as if on a map, on a blueprint, without any human landmark. We were in complete abstraction. Avenues and avenues, streets and streets. Here, there is no suburbs. Off-center areas are already some sort of lost suburbs, drowned into their own desert. All this seemed to be carved from emptiness, since on each side of these roads, too wide and so long, the moon was crushing imperceptible houses. As a matter of fact, the Argentineans still built houses like those in the colonial era. A façade, pierced with a door and two windows; above this, a baluster hiding the terraced roof - and that's all.

Everybody was asleep. The cinemas were closed, the cafés were blinking. Every two or three kilometers, the eerie brightness of a small whorehouse kept a lonely vigil.

O, feebleness of an electrical lightbulb, trembling and tinting, alone in the stone nightmare of a humanity shattered under stone.

My poet was walking, taking large and crazy strides. He was walking me amongst his despair and his love, because he loved this desolation he made his heart's.

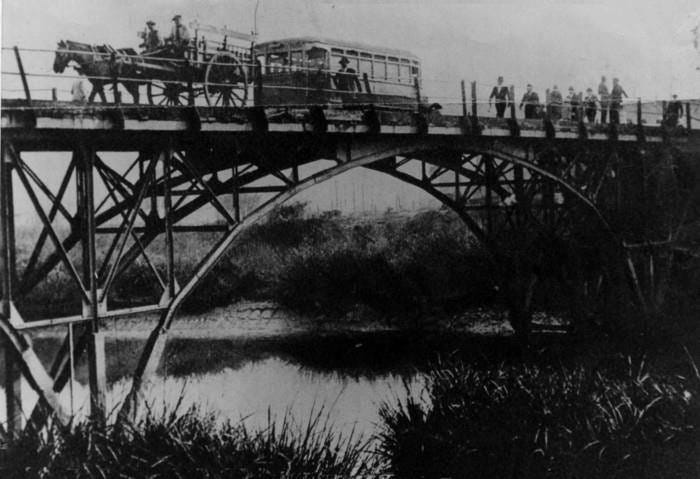

Finally, after three hours of this rush towards nothing, we arrived on a bridge. Borgès stopped. He had ended up finding something still pulsating in the middle of these lifeless stretches: a stream, keeping its name and its murmur from the colonial era, from the good old time, the time of things thriving.1

He was looking at me with a smile, satisfied. We knew eachother since this morning, but from one bank of the Ocean to the other, from one hemisphere to the other, we dreamt on the same stern books and on the same bird-brained cinema girls.

And then he was rewarded, because poets are always rewarded around three in the morning, in their quests defying the world's barrenness: we heard, over the stream's timid murmur, the more brazen and louder murmur of a guitar and, in a small cabaret, we found a sleepless working-class, sharing its miseries with eagerness.

However two million men were asleep. Two million Europeans, camping there, nostalgic.

This city there truly is the end of the world, it is the end of the horizon, because those who dwell here believe it. Deep down, they feel exiled from Europe.

That made me dream too; such an immense, improvised, unfinished city.

Here, two million Europeans who did not renounce their bad reasons were camping. There is an America that was made by love - the America of Puritans in the North, and that of Conquistadores in the South, who went there to protect their Faith, to quietly read their “Bible” for the first ones, as for the second ones, to spread their Faith, to have the Mass also said under the Southern Cross. But this America is forgotten, drowned into another, who went faithless, just to earn money.

I thus have dreamed a lot about money, loitering around these endless suburbs where hundreds of thousands failed millionnaires were piling up. Have these Europeans thought about money enough, in the last centuries! They did not come here to rediscover a nature that was lost in Europe. They did not come to realize the dream of Rousseau, to make themselves simple and strong again in the middle of the fields. They came to make money. That's all. Again, the crisis is there. It weighs down upon two million and a half men in this city, which is the capital of a country as big as Europe. And in this immense flat country, starting unexpectedly just behind the last house of this street, going from the South Pole to the Tropics, from the Atlantic to the Andes, it weighs upon eight million more men. And still, there's many of these eight million who live closeted in other large cities. Wheat and cattle, this doesn't need many men to get produced nowadays. And yet there still is too much, because what they produce doesn't get sold.

What makes one dream here is that it is the whole of Europe's history. The history of America is the history of Europe. Europe wanted to make money, so she made America. And Europe is sad and let down, in America.

She lives in uglyness and in spiritual deprivation. And gold now is nothing but paper. And there are men begging in the streets. At the door of the brand new Stock exchange of America, just as at the door of the old Stock exchange of Europe.

Disappointment, humiliation. Common to both America and Europe.

And either way, it is sad for a great modern city to only be modern. One has to have lived a few months in an American city to know about the past's worth. Just imagine that we'd only have nowadays' - so ugly - avenue des Champs-Elysées, and the excentric areas in Paris. The avenue des Champs-Elysées without the Arc de Triomphe on one end, without the Louvre on the other. Our ancestors sure are keeping us warm.

There were moments where I would yearn. I wanted to see a beautiful object. Not a museum there. There's a scanty museum where goes a Courbet or a Manet - very beautiful, by the way-, I don't even remember, that grounded there by accident; there is nothing.

Some concerts where foreign ensembles come and play Wagner, Debussy, Stravinsky. Yes, they do have music. But not a single theater. So, cinemas. But in Paris, cinema has a background. We have fun there, we get lulled. The snobs see things that are not there. But here, we see at once what cinema is. We tell ourselves, this is our civilisation!

I wasn't playing the fool. I knew quite well that the beautiful things in our museums, our concerts and our theaters are not more for us, Europeans of today, than for them, Americans.

After all, these people were still in Europe when we used to do something. They have a right, just as we have, to Notre-Dame and to Versailles - not more than us, not less than us.

A city where there is not a beautiful monument. In the corners, some pretty little houses from the colonial era, squeezed between two skycrapers, destined to the pickaxe.

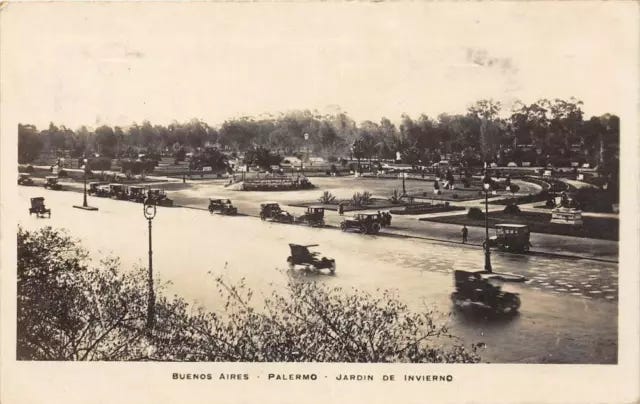

There is not even nature in this city. No park. A park, this long avenue, on the side of a railway, where the trees are pitiful?

There is a zoo, sure, but where the weird and charming animals of America are as lost as they are in Antwerp or Amsterdam.

Where to go? What to do? Let us go to the countryside. It is there, close, tremendous.

Yes, but... First, there are no roads. If you take a car, you will soon fall into the bogs. They have had neither the time nor the money to build the roads. And first the country is too big. It is expensive to build civilisation overnight, from scrap. Railroads were built, it is already quite a lot.

But take the train and disembark at a station randomly. There is no hotel, or it is not comely. And the village is not comely. Yet another campsite. Everything for work, for gain.

The pampa is like the Beauce, but without the bell towers, without old houses. Shanties thrown on a crossroad like some sort of aerodrome.

And the countryside is not fields or small pathways, but large properties. A property: a hundred square kilometers, perfectly flat, striped with iron wire.

On this immense, deep nature, a disappointing setting is thrown.

But nevermind. Here, there is a beauty, and austere, resisting beauty. Also heinous, devouring. Here, the flatness shows its magnitude. After all, flatness is the sea, you could swim into this green, with some green above your head, and the sky above it all. Then you would know the beauty of perdition of this country.

The beauty of Argentina is the very beauty of loneliness (solitude). Terrible beauty, in front of which most step back, most Argentineans who live in the cities around the cinemas.

One would need months and a horse to slowly tame this naked majesty, offering itself to you like a woman who does not wear any makeup, no bait, no coquetry; not even awaken, buried in its depth, who'd scorn taking you, who'd rather be taken...

But I come back and return to the cinema.

I bury myself in the center, where the streets are narrow. Wells between houses too high for their dark streets, like in the old New York.

I let go a story for another, a daydream for another.

Here piles up a humanity afraid to take the subway, because she knows she has to come out of it, and that it will lead to these endless avenues. So here we're piling up in bars, in cinemas. Here, we are bored.

But we nevertheless desire. Yes, we desire the vague. And desire, through accumulating, falls back on itself and creates an oppression.

O heavy desire, heavy, lost and sad desire of the European, of the man lost in this immense and numb trading post, turning his back despairingly, just another minute, to this nature where he'll have to surrender himself.

Because in the end, Argentina will need to renounce its dependency to Europe, to the great profits, and give in to living on herself. Then she will be forced to make up her own civilisation. It will be the redemption of her soul, recovery from the crisis, for her as for many countries.

Then the beauty of the pampa will get into Buenos-Aires.

Then Argentina will recover her genius, the savage and soft genius, rough and delicate that she started to flourish, before the arrival of emigrants, and that she now hides in the corners where still shivers a guitar, where a tango gets straightened up, where a sad man caresses a horse's neck.2

According to anthropologist Edgardo C. Krebs, the bridge they went to was the Puente Alsina: “There was a bridge in the outskirts of Buenos Aires, Puente Alsina, that stood between the last settlements and the “magic circle of the pampas.” After long walks that sometimes lasted most of the night, Borges often ended at the bridge. As in a ritual, he stood on it to experience the thrill of that border, the lights of the new city behind him; ahead, in darkness and silence, the tantalizing wilderness, a nonhuman presence that preceded the city and its inhabitants and would endure after their memory had been erased. Borges would take friends to the bridge to see how they reacted. When the French writer Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, after being subjected to the ritual, defined the pampas as “horizontal vertigo,” Borges was pleased. It had been left to a foreigner, he said, to find the perfect words that had eluded him, and many generations of Argentines.”

I want listen while tanning nudist walk, how do?